Why Do AI Agents Demo Well But Perform Poorly?

Editorial Team

Feb 11, 2026

Why Do AI Agents Demo Well But Perform Poorly?

In a recent keynote delivered at the Machines Can Think AI Summit 2026 in Abu Dhabi, Anton Anton Masalovich, the Head of ML Team at Aiphoria, made a point that many enterprise teams are discovering the hard way: building an AI agent that demos convincingly is easy, but deploying one that performs reliably in production is another thing entirely.

When AI agents fail in production, it’s rarely because the underlying model is “not smart enough.” Modern LLMs are already competent at language, intent recognition, and basic reasoning. They can converse fluently, summarize, explain, and follow instructions. In controlled demos, that intelligence is more than enough.

The real gap shows up after deployment, and it’s caused by a lack of discipline, not a lack of capability.

The missing pieces

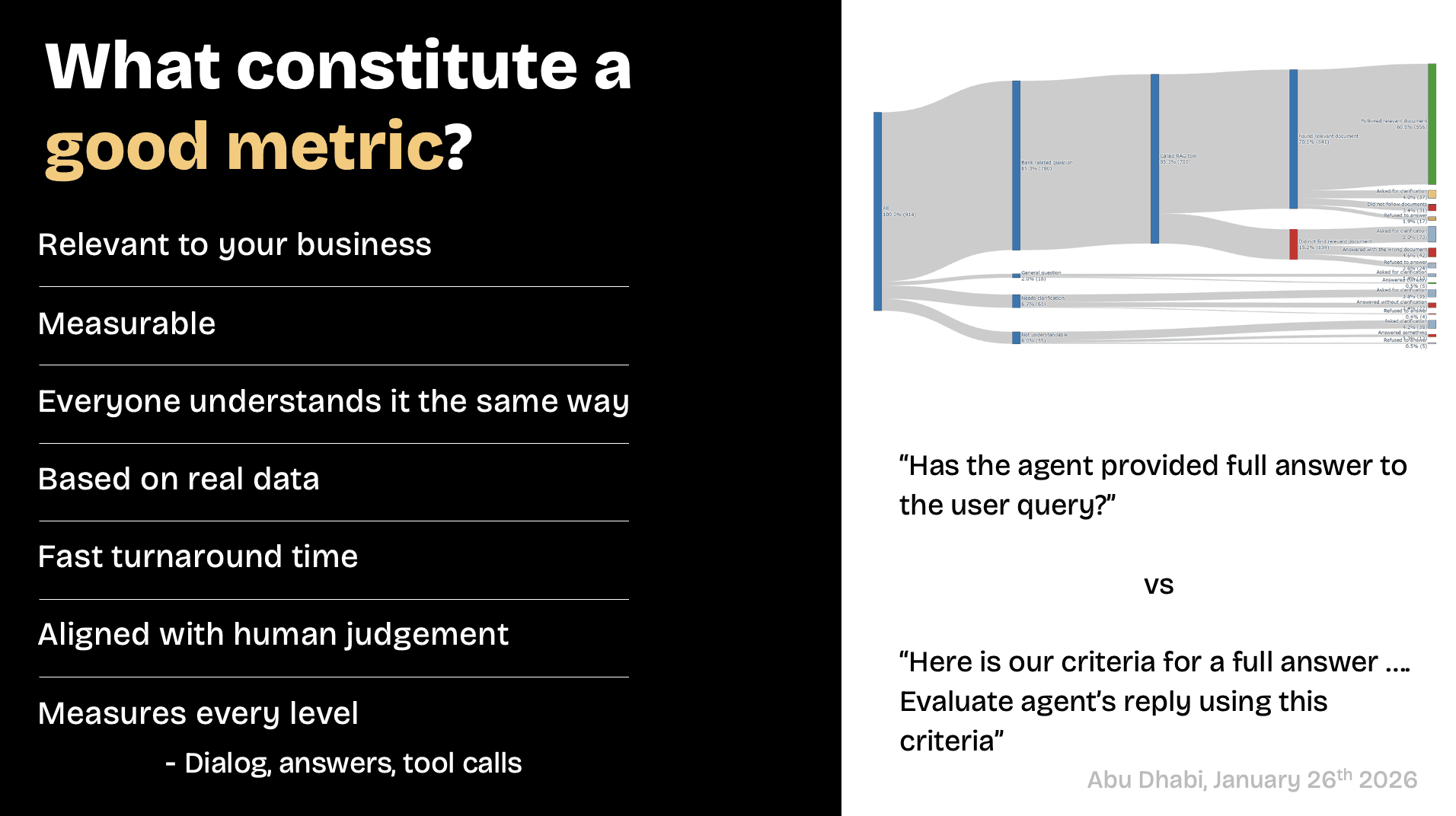

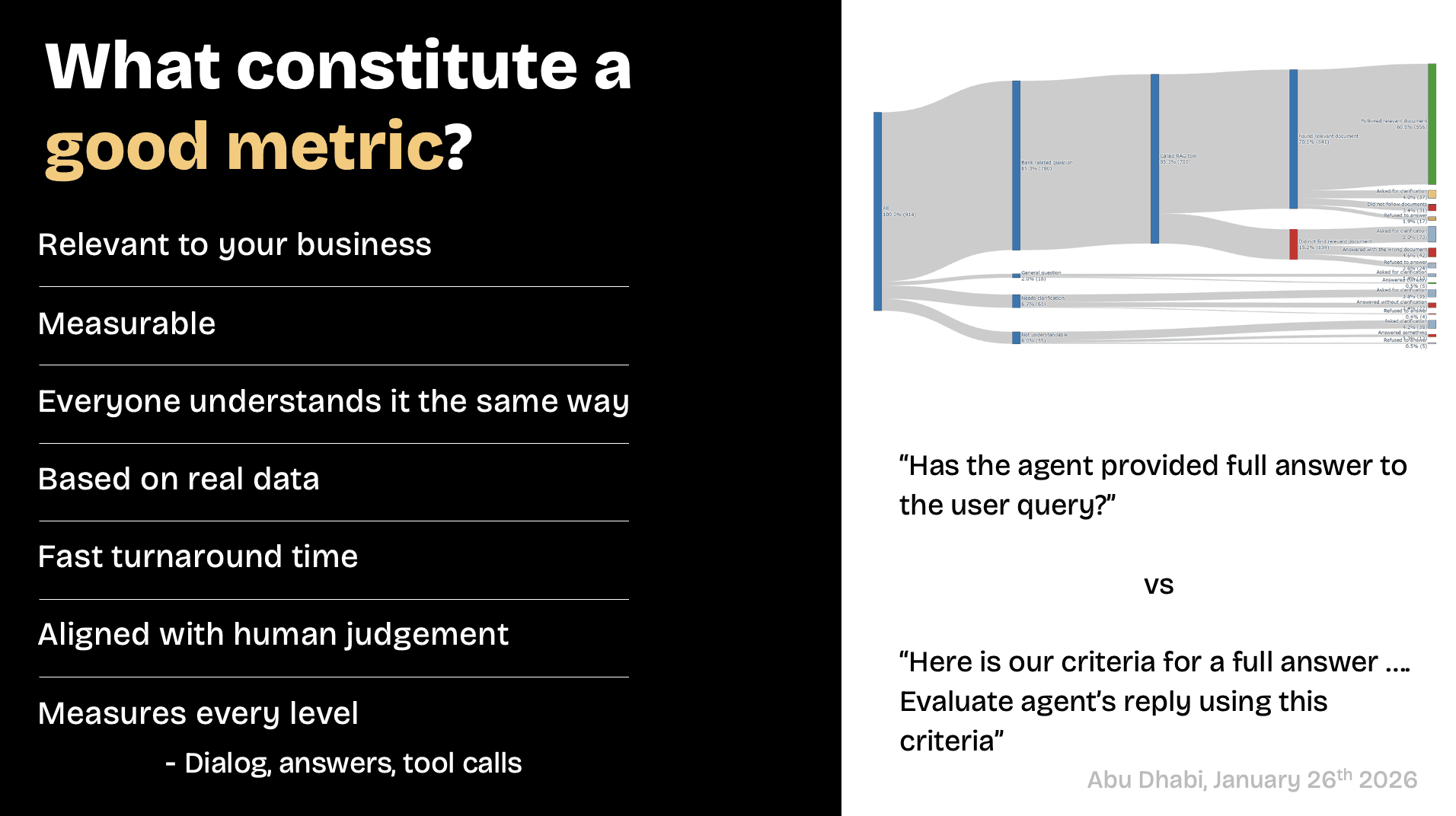

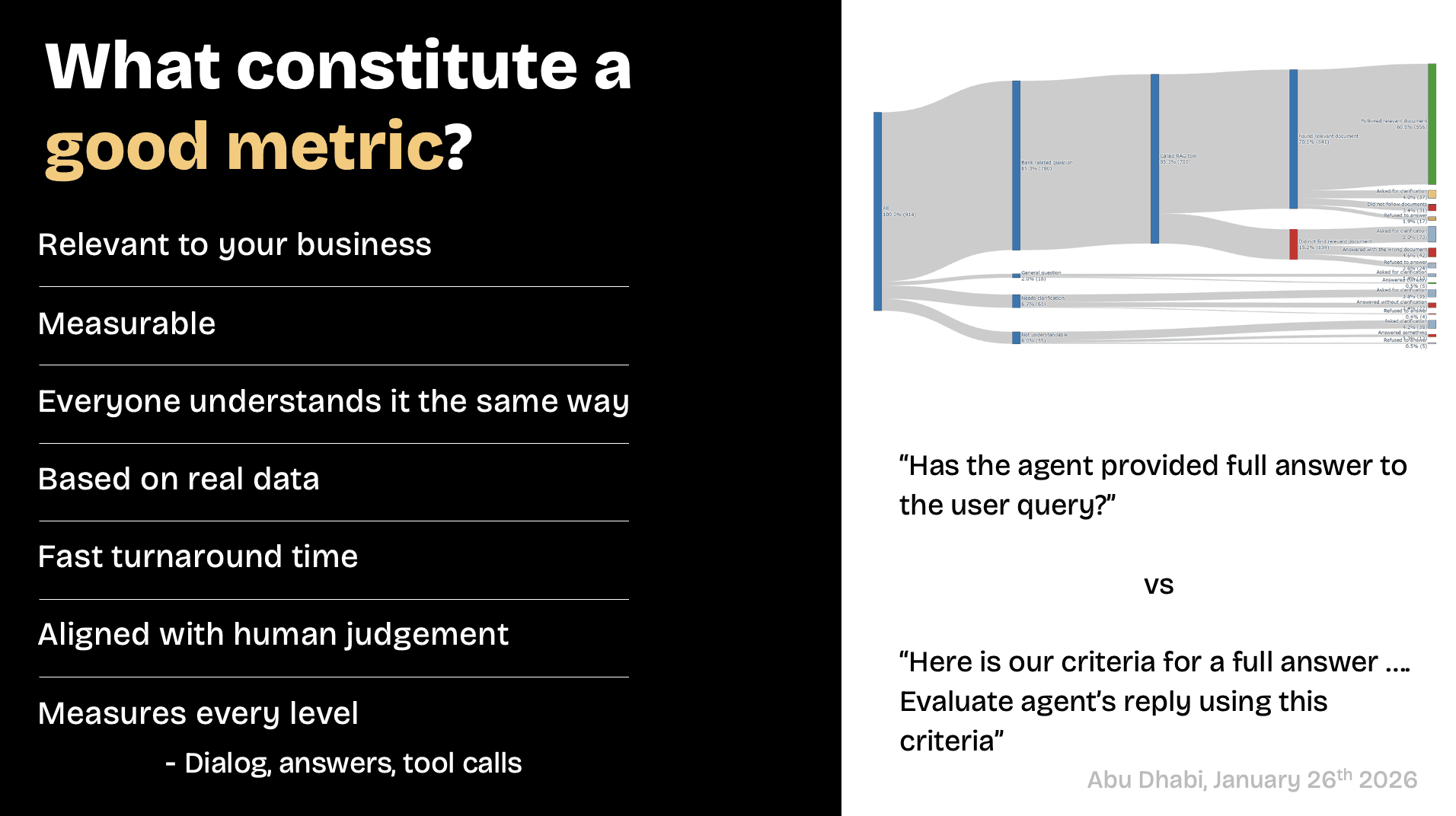

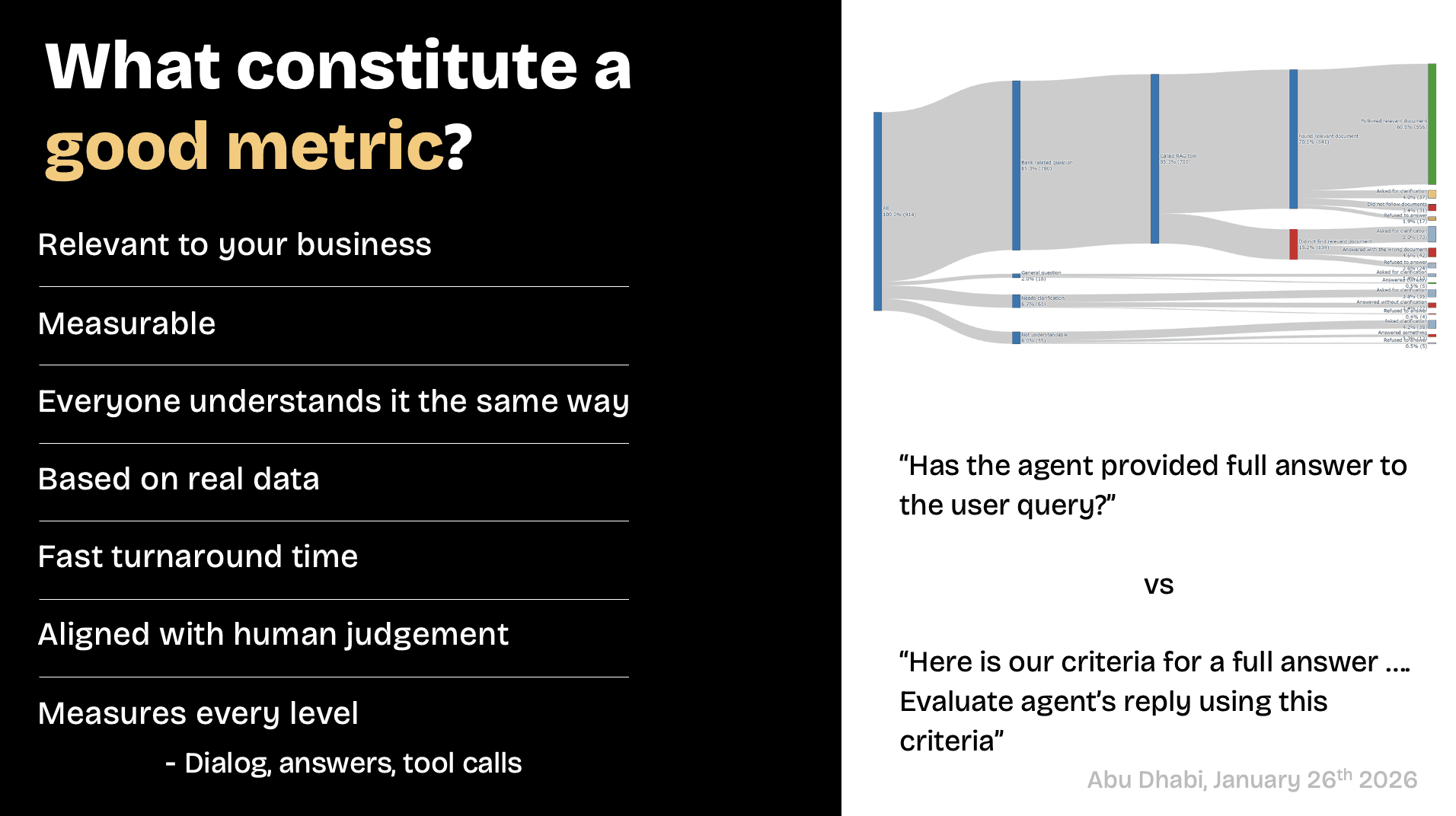

Metrics are the first missing element. Many teams never define what success looks like beyond “the agent sounds good.” Without clear outcome metrics – payments secured, issues resolved, escalations avoided, tasks completed – you cannot tell whether the agent is helping or hurting the business. Intelligence without measurement turns into opinion and guesswork.

Evaluation is the second issue. Agents are often tested casually or anecdotally, not systematically. Teams do not run agents through thousands of realistic scenarios, edge cases, or adversarial inputs. As a result, failures only surface when real customers encounter them. This is a testing failure, not an intelligence failure.

Controls are the third gap. Production AI needs guardrails: scoped tool access, input filtering, output moderation, identity verification outside the model, and deterministic fallbacks. When these are missing, even a highly capable model will behave unpredictably or dangerously. The issue is governance, not cognition.

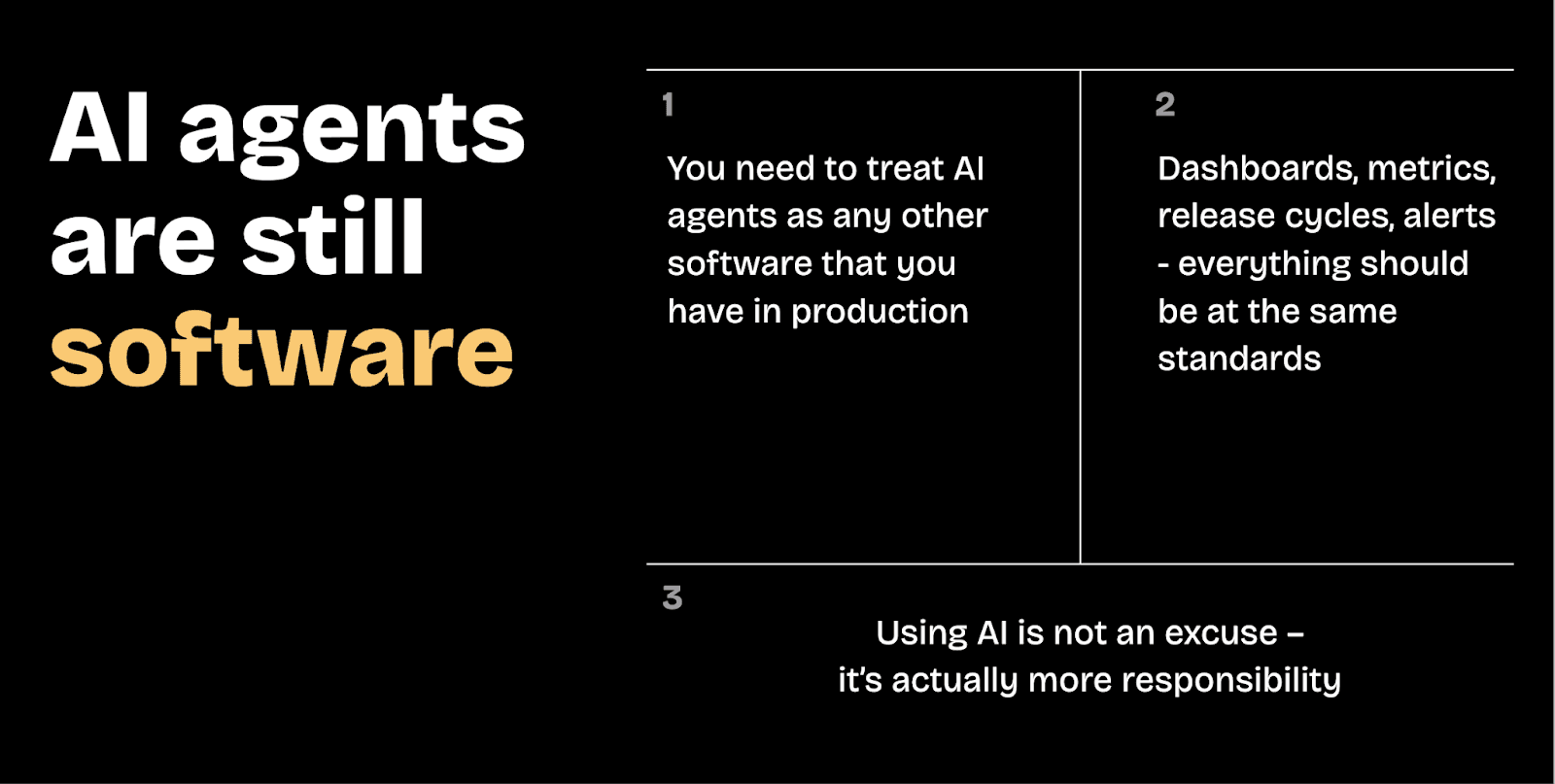

Finally, there’s a mindset problem. Many enterprises see AI as something magical or autonomous, rather than as a software component. Traditional software is versioned, tested, monitored, rolled back, and owned. AI agents? Often, don’t get the same due diligence. When teams stop applying software discipline, they shouldn’t be surprised when AI agents fail when deployed.

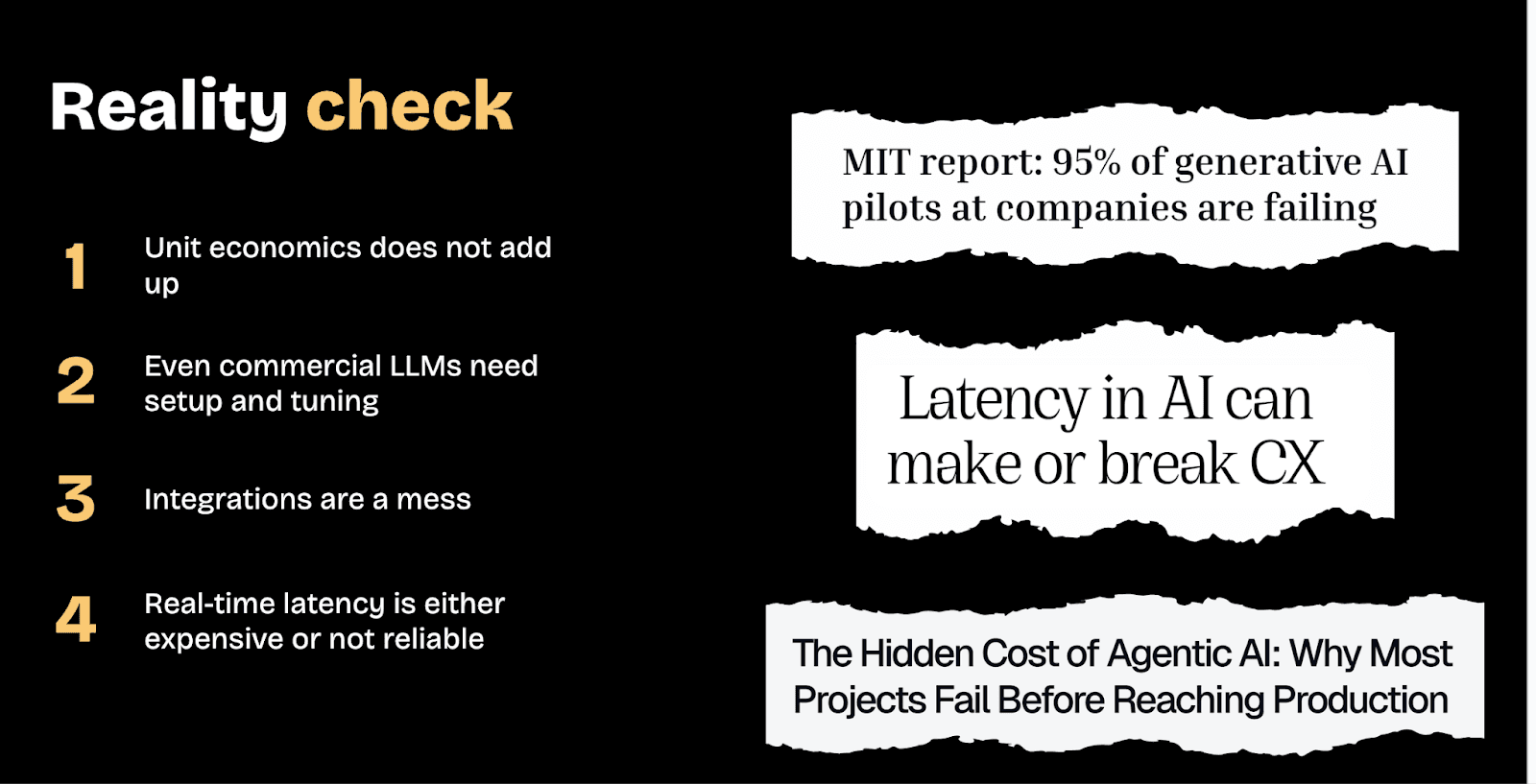

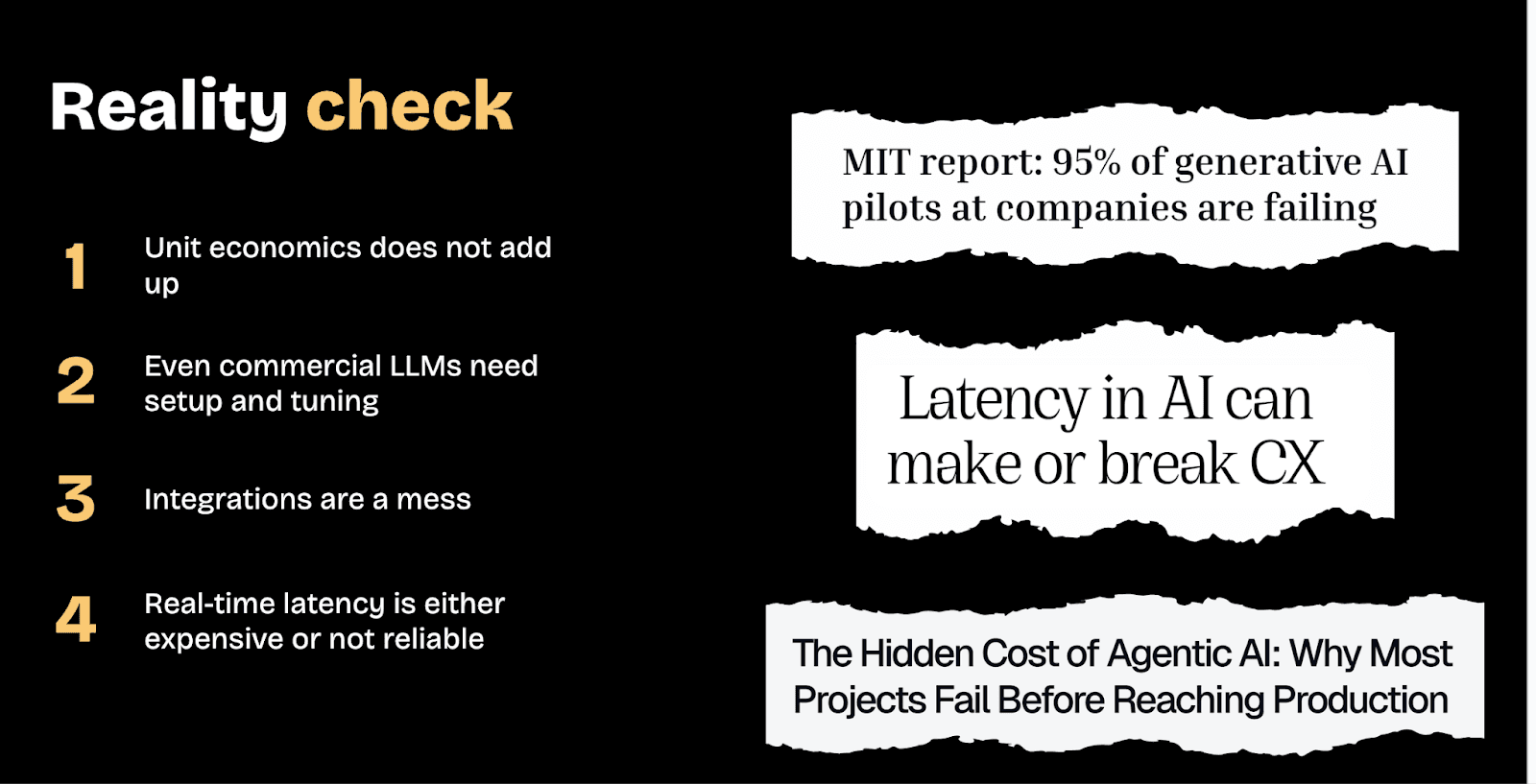

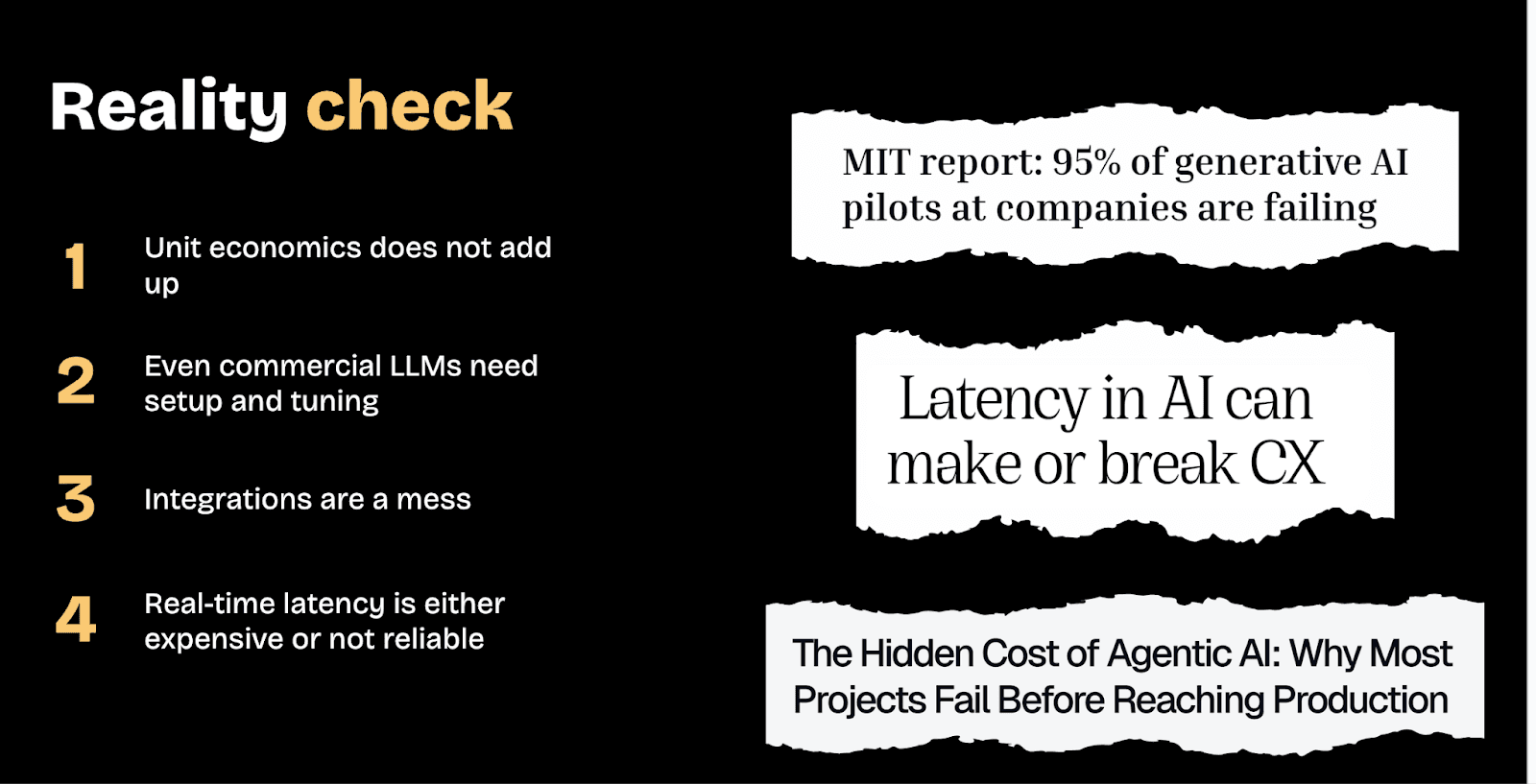

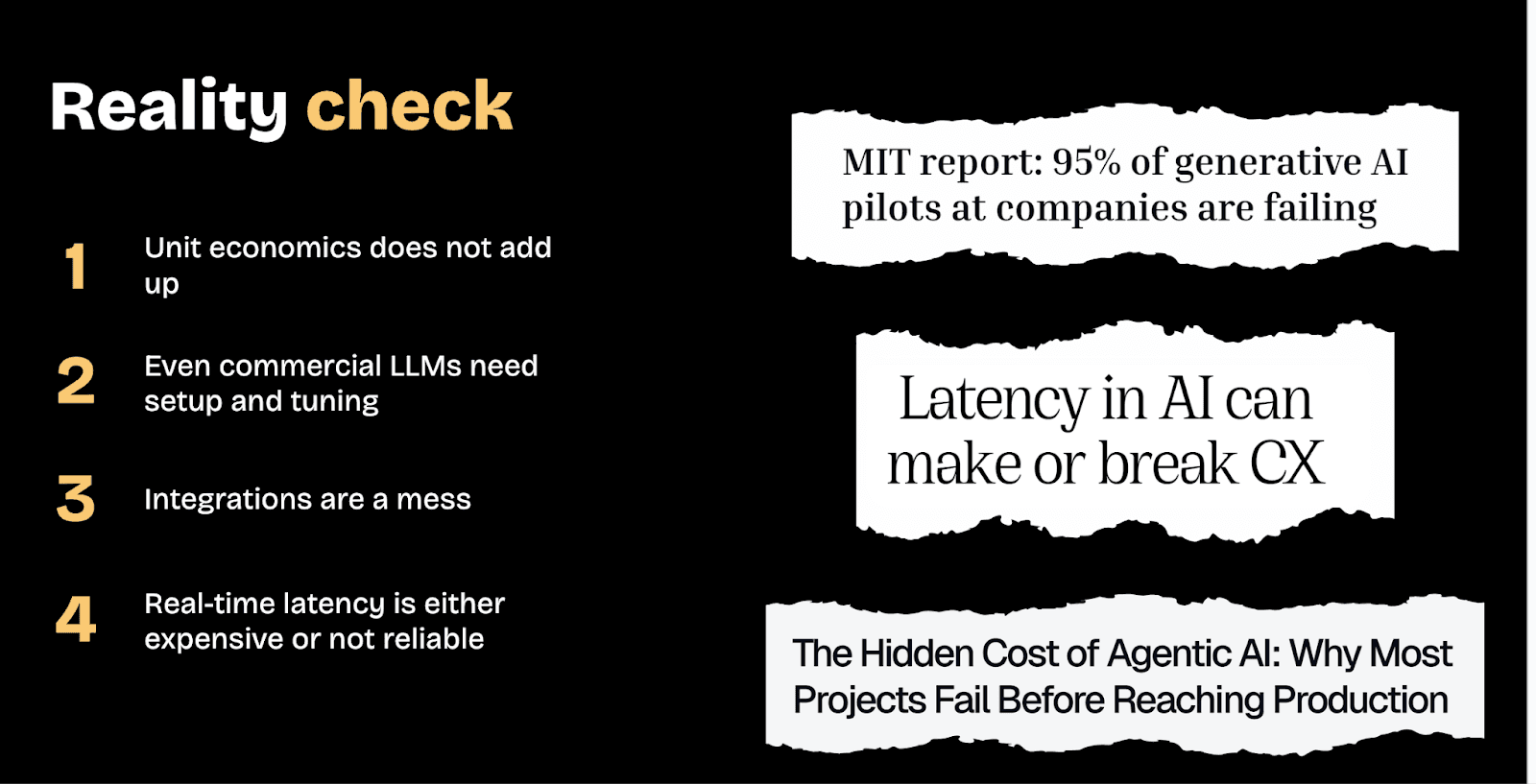

The hype problem: agents everywhere, outcomes nowhere

There’s a prevailing narrative that suggests AI agents are simple to deploy. Define a persona, connect a large language model, and launch within minutes! But in reality, most teams report the same problems once they move beyond pilots: latency is too high, costs spiral, integrations break, agents sound articulate but fail to complete the task that actually matters.

This is not a model problem. It’s a production problem.

Many teams skip the hard work required to make agents viable in real environments:

They do not instrument conversations.

They do not test against realistic user behavior.

They do not define success beyond vague satisfaction.

As soon as these agents meet real customers who interrupt, change direction, switch languages, or test boundaries, performance quickly degrades. Why should this surprise anyone?

Metrics first or do not ship at all

One of Anton’s strongest points was also the simplest: if you do not start with metrics, you’re just guessing. “It worked when I tried it” is not a performance signal.

Production-grade agents must be measured against concrete business outcomes. That means defining finish lines clearly: a payment collected, a promise to pay secured, an appointment booked, an issue resolved without escalation. These are not abstract goals but binary outcomes that can be measured.

Once those outcomes are defined, every step of the conversation must be observable. Did the agent correctly identify intent? Did it invoke the right tool? Did the tool return accurate data? Did the agent use that data correctly in its response?

Without this visibility, teams can only trade opinions with each other about why their AI agent isn’t performing properly. With it, they can run controlled experiments, change one variable at a time, replay thousands of conversations, and immediately see whether performance improved or regressed.

Changing the way agents are built

Historically, testing conversational systems required waiting for live traffic and manually reviewing transcripts. That process was slow, expensive, and subjective. Today, teams can generate large volumes of realistic synthetic conversations between simulated customers and agents, then score every step against defined criteria.

This approach fundamentally changes development for the better. Agents can be tested while being built, not weeks later in production. Changes can be validated across thousands of conversations instead of a handful of anecdotes. Regressions become immediately visible.

The caveat? Synthetic customers must absolutely reflect actual user behavior. Ambiguity, interruptions, partial information, emotional responses, and edge cases all matter. If synthetic testing avoids those realities, then it’s merely recreating the same blind spots that are bound to break agents.

Perception matters as much as correctness

A recurring theme in the keynote was that technical correctness does not guarantee user trust. For instance, an agent announced it was preparing a data visualization but sometimes failed to show one. Internally, the system was actually behaving as designed, but from the customer’s perspective? It was broken and even untrustworthy.

This distinction is critical. Customers don’t evaluate systems based on architectural intent. They judge consistency and clarity. If an agent claims to be doing something, it either must do it every time or explain clearly why it can’t. Anything else erodes confidence, even when backend metrics look healthy.

This is why evaluation must not focus solely on task completion. It has to account for perception. Does the agent behave predictably? Does it communicate limitations clearly? Does it reduce uncertainty instead of creating it?

Control is mandatory in regulated environments

Another reality we can’t ignore is adversarial behavior. AI agents will be tested by users, both intentionally and unintentionally. Jailbreaks, prompt manipulation, and social engineering attempts are routine. No production system can rely solely on an agent’s discretion.

Robust deployments require layered controls. In highly regulated sectors like banking or pharma, that’s especially critical. Inputs must be filtered, outputs must be moderated, and tool access must be tightly scoped. Identity verification and authorization must happen outside the agent, not inside it. The agent should receive only the information required to complete the task at hand.

In some situations, the right decision may be to entirely disable the AI. This doesn’t constitute a failure; it’s a sign of responsible engineering. Knowing when to fall back to deterministic workflows or human handling is part of building trustworthy systems.

Treat agents like software, not assistants

The most important takeaway is conceptual. AI agents are software components. They require versioning, testing, monitoring, rollback plans, and clear ownership. They’re not independently intelligent assistants that can be deployed and left alone.

Organizations that succeed build platforms around agents, not isolated scripts. They review metrics continuously. They test changes before release. They assume failures will occur and design systems that can detect and correct them quickly.

This mindset also explains why some teams intentionally limit deployments. Turning off an agent in a high-risk scenario is not anti-AI. It is pro-outcome.

The takeaways for enterprise leaders?

For leaders evaluating AI agents in customer operations, the implications are straightforward.

Start with business outcomes, not demos, and define success in measurable terms.

Invest in evaluation infrastructure. Synthetic testing and step-level metrics are no longer optional.

Design for user perception. Consistency and transparency matter as much as accuracy.

Build in control mechanisms from day one. Assume scrutiny and misuse.

Operate with software discipline. Agents require ongoing governance, not one-off configuration.

Teams that internalize these principles move beyond experimentation and pilot programs. They deploy AI agents that don’t just sound capable but reliably perform the job they were deployed to do.

Anton Shestakov

Why Do AI Agents Demo Well But Perform Poorly?

Editorial Team

Feb 11, 2026

Why Do AI Agents Demo Well But Perform Poorly?

In a recent keynote delivered at the Machines Can Think AI Summit 2026 in Abu Dhabi, Anton Anton Masalovich, the Head of ML Team at Aiphoria, made a point that many enterprise teams are discovering the hard way: building an AI agent that demos convincingly is easy, but deploying one that performs reliably in production is another thing entirely.

When AI agents fail in production, it’s rarely because the underlying model is “not smart enough.” Modern LLMs are already competent at language, intent recognition, and basic reasoning. They can converse fluently, summarize, explain, and follow instructions. In controlled demos, that intelligence is more than enough.

The real gap shows up after deployment, and it’s caused by a lack of discipline, not a lack of capability.

The missing pieces

Metrics are the first missing element. Many teams never define what success looks like beyond “the agent sounds good.” Without clear outcome metrics – payments secured, issues resolved, escalations avoided, tasks completed – you cannot tell whether the agent is helping or hurting the business. Intelligence without measurement turns into opinion and guesswork.

Evaluation is the second issue. Agents are often tested casually or anecdotally, not systematically. Teams do not run agents through thousands of realistic scenarios, edge cases, or adversarial inputs. As a result, failures only surface when real customers encounter them. This is a testing failure, not an intelligence failure.

Controls are the third gap. Production AI needs guardrails: scoped tool access, input filtering, output moderation, identity verification outside the model, and deterministic fallbacks. When these are missing, even a highly capable model will behave unpredictably or dangerously. The issue is governance, not cognition.

Finally, there’s a mindset problem. Many enterprises see AI as something magical or autonomous, rather than as a software component. Traditional software is versioned, tested, monitored, rolled back, and owned. AI agents? Often, don’t get the same due diligence. When teams stop applying software discipline, they shouldn’t be surprised when AI agents fail when deployed.

The hype problem: agents everywhere, outcomes nowhere

There’s a prevailing narrative that suggests AI agents are simple to deploy. Define a persona, connect a large language model, and launch within minutes! But in reality, most teams report the same problems once they move beyond pilots: latency is too high, costs spiral, integrations break, agents sound articulate but fail to complete the task that actually matters.

This is not a model problem. It’s a production problem.

Many teams skip the hard work required to make agents viable in real environments:

They do not instrument conversations.

They do not test against realistic user behavior.

They do not define success beyond vague satisfaction.

As soon as these agents meet real customers who interrupt, change direction, switch languages, or test boundaries, performance quickly degrades. Why should this surprise anyone?

Metrics first or do not ship at all

One of Anton’s strongest points was also the simplest: if you do not start with metrics, you’re just guessing. “It worked when I tried it” is not a performance signal.

Production-grade agents must be measured against concrete business outcomes. That means defining finish lines clearly: a payment collected, a promise to pay secured, an appointment booked, an issue resolved without escalation. These are not abstract goals but binary outcomes that can be measured.

Once those outcomes are defined, every step of the conversation must be observable. Did the agent correctly identify intent? Did it invoke the right tool? Did the tool return accurate data? Did the agent use that data correctly in its response?

Without this visibility, teams can only trade opinions with each other about why their AI agent isn’t performing properly. With it, they can run controlled experiments, change one variable at a time, replay thousands of conversations, and immediately see whether performance improved or regressed.

Changing the way agents are built

Historically, testing conversational systems required waiting for live traffic and manually reviewing transcripts. That process was slow, expensive, and subjective. Today, teams can generate large volumes of realistic synthetic conversations between simulated customers and agents, then score every step against defined criteria.

This approach fundamentally changes development for the better. Agents can be tested while being built, not weeks later in production. Changes can be validated across thousands of conversations instead of a handful of anecdotes. Regressions become immediately visible.

The caveat? Synthetic customers must absolutely reflect actual user behavior. Ambiguity, interruptions, partial information, emotional responses, and edge cases all matter. If synthetic testing avoids those realities, then it’s merely recreating the same blind spots that are bound to break agents.

Perception matters as much as correctness

A recurring theme in the keynote was that technical correctness does not guarantee user trust. For instance, an agent announced it was preparing a data visualization but sometimes failed to show one. Internally, the system was actually behaving as designed, but from the customer’s perspective? It was broken and even untrustworthy.

This distinction is critical. Customers don’t evaluate systems based on architectural intent. They judge consistency and clarity. If an agent claims to be doing something, it either must do it every time or explain clearly why it can’t. Anything else erodes confidence, even when backend metrics look healthy.

This is why evaluation must not focus solely on task completion. It has to account for perception. Does the agent behave predictably? Does it communicate limitations clearly? Does it reduce uncertainty instead of creating it?

Control is mandatory in regulated environments

Another reality we can’t ignore is adversarial behavior. AI agents will be tested by users, both intentionally and unintentionally. Jailbreaks, prompt manipulation, and social engineering attempts are routine. No production system can rely solely on an agent’s discretion.

Robust deployments require layered controls. In highly regulated sectors like banking or pharma, that’s especially critical. Inputs must be filtered, outputs must be moderated, and tool access must be tightly scoped. Identity verification and authorization must happen outside the agent, not inside it. The agent should receive only the information required to complete the task at hand.

In some situations, the right decision may be to entirely disable the AI. This doesn’t constitute a failure; it’s a sign of responsible engineering. Knowing when to fall back to deterministic workflows or human handling is part of building trustworthy systems.

Treat agents like software, not assistants

The most important takeaway is conceptual. AI agents are software components. They require versioning, testing, monitoring, rollback plans, and clear ownership. They’re not independently intelligent assistants that can be deployed and left alone.

Organizations that succeed build platforms around agents, not isolated scripts. They review metrics continuously. They test changes before release. They assume failures will occur and design systems that can detect and correct them quickly.

This mindset also explains why some teams intentionally limit deployments. Turning off an agent in a high-risk scenario is not anti-AI. It is pro-outcome.

The takeaways for enterprise leaders?

For leaders evaluating AI agents in customer operations, the implications are straightforward.

Start with business outcomes, not demos, and define success in measurable terms.

Invest in evaluation infrastructure. Synthetic testing and step-level metrics are no longer optional.

Design for user perception. Consistency and transparency matter as much as accuracy.

Build in control mechanisms from day one. Assume scrutiny and misuse.

Operate with software discipline. Agents require ongoing governance, not one-off configuration.

Teams that internalize these principles move beyond experimentation and pilot programs. They deploy AI agents that don’t just sound capable but reliably perform the job they were deployed to do.

Anton Shestakov

Why Do AI Agents Demo Well But Perform Poorly?

Why Do AI Agents Demo Well But Perform Poorly?

Editorial Team

Feb 11, 2026

Why Do AI Agents Demo Well But Perform Poorly?

In a recent keynote delivered at the Machines Can Think AI Summit 2026 in Abu Dhabi, Anton Anton Masalovich, the Head of ML Team at Aiphoria, made a point that many enterprise teams are discovering the hard way: building an AI agent that demos convincingly is easy, but deploying one that performs reliably in production is another thing entirely.

When AI agents fail in production, it’s rarely because the underlying model is “not smart enough.” Modern LLMs are already competent at language, intent recognition, and basic reasoning. They can converse fluently, summarize, explain, and follow instructions. In controlled demos, that intelligence is more than enough.

The real gap shows up after deployment, and it’s caused by a lack of discipline, not a lack of capability.

The missing pieces

Metrics are the first missing element. Many teams never define what success looks like beyond “the agent sounds good.” Without clear outcome metrics – payments secured, issues resolved, escalations avoided, tasks completed – you cannot tell whether the agent is helping or hurting the business. Intelligence without measurement turns into opinion and guesswork.

Evaluation is the second issue. Agents are often tested casually or anecdotally, not systematically. Teams do not run agents through thousands of realistic scenarios, edge cases, or adversarial inputs. As a result, failures only surface when real customers encounter them. This is a testing failure, not an intelligence failure.

Controls are the third gap. Production AI needs guardrails: scoped tool access, input filtering, output moderation, identity verification outside the model, and deterministic fallbacks. When these are missing, even a highly capable model will behave unpredictably or dangerously. The issue is governance, not cognition.

Finally, there’s a mindset problem. Many enterprises see AI as something magical or autonomous, rather than as a software component. Traditional software is versioned, tested, monitored, rolled back, and owned. AI agents? Often, don’t get the same due diligence. When teams stop applying software discipline, they shouldn’t be surprised when AI agents fail when deployed.

The hype problem: agents everywhere, outcomes nowhere

There’s a prevailing narrative that suggests AI agents are simple to deploy. Define a persona, connect a large language model, and launch within minutes! But in reality, most teams report the same problems once they move beyond pilots: latency is too high, costs spiral, integrations break, agents sound articulate but fail to complete the task that actually matters.

This is not a model problem. It’s a production problem.

Many teams skip the hard work required to make agents viable in real environments:

They do not instrument conversations.

They do not test against realistic user behavior.

They do not define success beyond vague satisfaction.

As soon as these agents meet real customers who interrupt, change direction, switch languages, or test boundaries, performance quickly degrades. Why should this surprise anyone?

Metrics first or do not ship at all

One of Anton’s strongest points was also the simplest: if you do not start with metrics, you’re just guessing. “It worked when I tried it” is not a performance signal.

Production-grade agents must be measured against concrete business outcomes. That means defining finish lines clearly: a payment collected, a promise to pay secured, an appointment booked, an issue resolved without escalation. These are not abstract goals but binary outcomes that can be measured.

Once those outcomes are defined, every step of the conversation must be observable. Did the agent correctly identify intent? Did it invoke the right tool? Did the tool return accurate data? Did the agent use that data correctly in its response?

Without this visibility, teams can only trade opinions with each other about why their AI agent isn’t performing properly. With it, they can run controlled experiments, change one variable at a time, replay thousands of conversations, and immediately see whether performance improved or regressed.

Changing the way agents are built

Historically, testing conversational systems required waiting for live traffic and manually reviewing transcripts. That process was slow, expensive, and subjective. Today, teams can generate large volumes of realistic synthetic conversations between simulated customers and agents, then score every step against defined criteria.

This approach fundamentally changes development for the better. Agents can be tested while being built, not weeks later in production. Changes can be validated across thousands of conversations instead of a handful of anecdotes. Regressions become immediately visible.

The caveat? Synthetic customers must absolutely reflect actual user behavior. Ambiguity, interruptions, partial information, emotional responses, and edge cases all matter. If synthetic testing avoids those realities, then it’s merely recreating the same blind spots that are bound to break agents.

Perception matters as much as correctness

A recurring theme in the keynote was that technical correctness does not guarantee user trust. For instance, an agent announced it was preparing a data visualization but sometimes failed to show one. Internally, the system was actually behaving as designed, but from the customer’s perspective? It was broken and even untrustworthy.

This distinction is critical. Customers don’t evaluate systems based on architectural intent. They judge consistency and clarity. If an agent claims to be doing something, it either must do it every time or explain clearly why it can’t. Anything else erodes confidence, even when backend metrics look healthy.

This is why evaluation must not focus solely on task completion. It has to account for perception. Does the agent behave predictably? Does it communicate limitations clearly? Does it reduce uncertainty instead of creating it?

Control is mandatory in regulated environments

Another reality we can’t ignore is adversarial behavior. AI agents will be tested by users, both intentionally and unintentionally. Jailbreaks, prompt manipulation, and social engineering attempts are routine. No production system can rely solely on an agent’s discretion.

Robust deployments require layered controls. In highly regulated sectors like banking or pharma, that’s especially critical. Inputs must be filtered, outputs must be moderated, and tool access must be tightly scoped. Identity verification and authorization must happen outside the agent, not inside it. The agent should receive only the information required to complete the task at hand.

In some situations, the right decision may be to entirely disable the AI. This doesn’t constitute a failure; it’s a sign of responsible engineering. Knowing when to fall back to deterministic workflows or human handling is part of building trustworthy systems.

Treat agents like software, not assistants

The most important takeaway is conceptual. AI agents are software components. They require versioning, testing, monitoring, rollback plans, and clear ownership. They’re not independently intelligent assistants that can be deployed and left alone.

Organizations that succeed build platforms around agents, not isolated scripts. They review metrics continuously. They test changes before release. They assume failures will occur and design systems that can detect and correct them quickly.

This mindset also explains why some teams intentionally limit deployments. Turning off an agent in a high-risk scenario is not anti-AI. It is pro-outcome.

The takeaways for enterprise leaders?

For leaders evaluating AI agents in customer operations, the implications are straightforward.

Start with business outcomes, not demos, and define success in measurable terms.

Invest in evaluation infrastructure. Synthetic testing and step-level metrics are no longer optional.

Design for user perception. Consistency and transparency matter as much as accuracy.

Build in control mechanisms from day one. Assume scrutiny and misuse.

Operate with software discipline. Agents require ongoing governance, not one-off configuration.

Teams that internalize these principles move beyond experimentation and pilot programs. They deploy AI agents that don’t just sound capable but reliably perform the job they were deployed to do.

Why Do AI Agents Demo Well But Perform Poorly?

In a recent keynote delivered at the Machines Can Think AI Summit 2026 in Abu Dhabi, Anton Anton Masalovich, the Head of ML Team at Aiphoria, made a point that many enterprise teams are discovering the hard way: building an AI agent that demos convincingly is easy, but deploying one that performs reliably in production is another thing entirely.

When AI agents fail in production, it’s rarely because the underlying model is “not smart enough.” Modern LLMs are already competent at language, intent recognition, and basic reasoning. They can converse fluently, summarize, explain, and follow instructions. In controlled demos, that intelligence is more than enough.

The real gap shows up after deployment, and it’s caused by a lack of discipline, not a lack of capability.

The missing pieces

Metrics are the first missing element. Many teams never define what success looks like beyond “the agent sounds good.” Without clear outcome metrics – payments secured, issues resolved, escalations avoided, tasks completed – you cannot tell whether the agent is helping or hurting the business. Intelligence without measurement turns into opinion and guesswork.

Evaluation is the second issue. Agents are often tested casually or anecdotally, not systematically. Teams do not run agents through thousands of realistic scenarios, edge cases, or adversarial inputs. As a result, failures only surface when real customers encounter them. This is a testing failure, not an intelligence failure.

Controls are the third gap. Production AI needs guardrails: scoped tool access, input filtering, output moderation, identity verification outside the model, and deterministic fallbacks. When these are missing, even a highly capable model will behave unpredictably or dangerously. The issue is governance, not cognition.

Finally, there’s a mindset problem. Many enterprises see AI as something magical or autonomous, rather than as a software component. Traditional software is versioned, tested, monitored, rolled back, and owned. AI agents? Often, don’t get the same due diligence. When teams stop applying software discipline, they shouldn’t be surprised when AI agents fail when deployed.

The hype problem: agents everywhere, outcomes nowhere

There’s a prevailing narrative that suggests AI agents are simple to deploy. Define a persona, connect a large language model, and launch within minutes! But in reality, most teams report the same problems once they move beyond pilots: latency is too high, costs spiral, integrations break, agents sound articulate but fail to complete the task that actually matters.

This is not a model problem. It’s a production problem.

Many teams skip the hard work required to make agents viable in real environments:

They do not instrument conversations.

They do not test against realistic user behavior.

They do not define success beyond vague satisfaction.

As soon as these agents meet real customers who interrupt, change direction, switch languages, or test boundaries, performance quickly degrades. Why should this surprise anyone?

Metrics first or do not ship at all

One of Anton’s strongest points was also the simplest: if you do not start with metrics, you’re just guessing. “It worked when I tried it” is not a performance signal.

Production-grade agents must be measured against concrete business outcomes. That means defining finish lines clearly: a payment collected, a promise to pay secured, an appointment booked, an issue resolved without escalation. These are not abstract goals but binary outcomes that can be measured.

Once those outcomes are defined, every step of the conversation must be observable. Did the agent correctly identify intent? Did it invoke the right tool? Did the tool return accurate data? Did the agent use that data correctly in its response?

Without this visibility, teams can only trade opinions with each other about why their AI agent isn’t performing properly. With it, they can run controlled experiments, change one variable at a time, replay thousands of conversations, and immediately see whether performance improved or regressed.

Changing the way agents are built

Historically, testing conversational systems required waiting for live traffic and manually reviewing transcripts. That process was slow, expensive, and subjective. Today, teams can generate large volumes of realistic synthetic conversations between simulated customers and agents, then score every step against defined criteria.

This approach fundamentally changes development for the better. Agents can be tested while being built, not weeks later in production. Changes can be validated across thousands of conversations instead of a handful of anecdotes. Regressions become immediately visible.

The caveat? Synthetic customers must absolutely reflect actual user behavior. Ambiguity, interruptions, partial information, emotional responses, and edge cases all matter. If synthetic testing avoids those realities, then it’s merely recreating the same blind spots that are bound to break agents.

Perception matters as much as correctness

A recurring theme in the keynote was that technical correctness does not guarantee user trust. For instance, an agent announced it was preparing a data visualization but sometimes failed to show one. Internally, the system was actually behaving as designed, but from the customer’s perspective? It was broken and even untrustworthy.

This distinction is critical. Customers don’t evaluate systems based on architectural intent. They judge consistency and clarity. If an agent claims to be doing something, it either must do it every time or explain clearly why it can’t. Anything else erodes confidence, even when backend metrics look healthy.

This is why evaluation must not focus solely on task completion. It has to account for perception. Does the agent behave predictably? Does it communicate limitations clearly? Does it reduce uncertainty instead of creating it?

Control is mandatory in regulated environments

Another reality we can’t ignore is adversarial behavior. AI agents will be tested by users, both intentionally and unintentionally. Jailbreaks, prompt manipulation, and social engineering attempts are routine. No production system can rely solely on an agent’s discretion.

Robust deployments require layered controls. In highly regulated sectors like banking or pharma, that’s especially critical. Inputs must be filtered, outputs must be moderated, and tool access must be tightly scoped. Identity verification and authorization must happen outside the agent, not inside it. The agent should receive only the information required to complete the task at hand.

In some situations, the right decision may be to entirely disable the AI. This doesn’t constitute a failure; it’s a sign of responsible engineering. Knowing when to fall back to deterministic workflows or human handling is part of building trustworthy systems.

Treat agents like software, not assistants

The most important takeaway is conceptual. AI agents are software components. They require versioning, testing, monitoring, rollback plans, and clear ownership. They’re not independently intelligent assistants that can be deployed and left alone.

Organizations that succeed build platforms around agents, not isolated scripts. They review metrics continuously. They test changes before release. They assume failures will occur and design systems that can detect and correct them quickly.

This mindset also explains why some teams intentionally limit deployments. Turning off an agent in a high-risk scenario is not anti-AI. It is pro-outcome.

The takeaways for enterprise leaders?

For leaders evaluating AI agents in customer operations, the implications are straightforward.

Start with business outcomes, not demos, and define success in measurable terms.

Invest in evaluation infrastructure. Synthetic testing and step-level metrics are no longer optional.

Design for user perception. Consistency and transparency matter as much as accuracy.

Build in control mechanisms from day one. Assume scrutiny and misuse.

Operate with software discipline. Agents require ongoing governance, not one-off configuration.

Teams that internalize these principles move beyond experimentation and pilot programs. They deploy AI agents that don’t just sound capable but reliably perform the job they were deployed to do.

Editorial Team